When Janice Ruize Guo got her first look at the Hoowa Supermarket that her new student friends had been telling her about, she was disappointed. Even with aisles, shelves and coolers devoted to spiky pink dragon fruit, long cream-colored lotus roots, dumplings, dried mushrooms, noodles, sauces, tea, sweet crackers sprinkled with seaweed and shrimp-flavored chips, it wasn’t what she imagined.

There weren’t the usual thousands of options like there were in markets near her home in Shanghai.

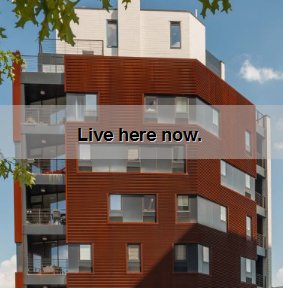

Instead of the polished Wegmans-style stores she was used to in her city of 23 million, the Hoowa seemed small, worn and lived in. The squat one-story store on Sheridan Drive, near Bailey Avenue, almost disappears beneath the big SUPERMARKET sign posted high on the outside of a nearby building. It is surrounded by asphalt on a long, treeless stretch of malls, chain stores and plazas with brighter, electric signs.

Eventually, though, it became an irresistible, essential ingredient for making Buffalo feel like home.

About every other week, Guo would shop at the Hoowa for a supply of solace, edible fun and the things she needed for her favorite bubbling hot pot soup.

“It’s one part of my life here,” said Guo, 26. A graduate student studying to teach English in China, she picked “Janice” as her English name because she liked its sound. She has straight bangs and a serious look that breaks into a smile when she considers something she’s fond of. “Sometimes I need dumplings.”

Beyond the front door and a shelf of lucky green bamboo shoots is the store’s heart — freezers full of dumplings in chicken, pork and tofu, and the rows of low shelves of produce the Hoowa owners drive in by the fresh truck-full from New York City markets, warehouses and docks Wednesday nights.

Guo had affection for the fruit and vegetable emissaries from her faraway home and the people she often missed — even for the ones she wasn’t especially interested in eating: Orange-red persimmon fruit with the taste of mango that Guo’s father likes. The mild Chinese yam her mother and aunties adore. Bitter gourd, too bitter for her, that some stuff with meat and then steam. The crisp, sweet and watery Asian pears that are her favorite.

Ginger, garlic, green onions. Good for cooking meat. Cilantro for on top of noodles. Cabbage for eating with pork. Chives with buds at the tips. Bok choy looking dressed up with clean white stems and bright green leaves. Sweet potato she slices up for a hot pot dinner.

Buffalo may be the second-biggest city in the state. But with its empty downtown and sprawling, skyscraper-free suburbs, it felt small compared with home, where the Yangtze River flows into the China Sea and the city teems with food of all kinds that she couldn’t help but miss.

A famous Chinese saying explains it this way: “People consider food like heaven.”

For the Hoowa’s delicacies, some local people with Asian roots — 25,000 at last count — time their shopping to when the truck arrives with the week’s delivery.

Even though owner Jet Ni tells them not to bother coming until after 7 p.m. when everything is unloaded, they come anyway.

On one recent Wednesday evening, the lines to the two cash registers were six or seven deep. “I often tell my husband, ‘Without this market I would already go back to China,’‚” said Lili Tian, a professor of biostatistics at the University at Buffalo.

Her shopping cart was nearly full. There was a lotus root that she slices up to cook with pork and a pile of six packages of tofu she uses for soups and stir fries. At $1.50, it’s just about half the price of other grocery stores.

She lifted up a package of clear, dried curls of jellyfish and then set it down as if explaining its appeal might be too complicated. She tried a bag of reddish dried dates, which she eats in rice or plain. “Good for women’s health,” she smiled.

She had considered some of the sweet, golden-yellow buns fresh from a bakery in New York City that her son likes. The selection of the Chinese version of doughnuts, filled with sweet bean paste, coconut and butter cream, seemed less than usual.

“I was late today,” said Tian.

Ni surveyed the pastry counter. At 85 cents a bun, he makes only five cents on each sale, but when he tried to drop them, students complained and he doesn’t want to disappoint.

“That’s what they use for breakfast,” he said.

To bring these and other kinds of “food heaven” here, every Monday at about noon, he climbs into his truck and heads for New York City.

The Ni family opened the market in 1998, partly out of frustration with their own trips to New York City. Food would sometimes spoil on the long bus trip back.

The Hoowa is named for their old home in China. It translates roughly as “expatriots from Fuzhou,” the provincial capital city near their village.

In the decade since Ni, a 1999 Sweet Home High School graduate, left his studies at UB to join the family business, it grew. They went from using a minivan to a big van, to a small truck, then to a big commercial truck.

The father of three young children, he likes the quiet thinking time he gets on the Monday drives (he took over when his father’s eyesight faltered). He spends the night in an apartment he keeps in Chinatown and shops from warehouses in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Long Island City.

Produce and fish come last.

Before dawn on Wednesdays, men fetch his orders from boats at the New York City pier. By the time he is heading home, he is eager to see his children, who call all the time when he’s not there.

For him, a measure of happiness and success is behind the pastries and a stack of fat, 25-pound “Family Elephant” bags of jasmine rice ($21): The table beneath a TV that plays Chinese news where the Nis gather for meal breaks.

“I still have all my family together,” he said. “That’s what I care about the most.”

People from other Asian cultures have been finding happiness here, too. He carries Japanese noodles, Thai jackfruit (big like a pineapple with a sweet and crispy taste), Korean spiced pickled kimchi cabbage and bony Vietnamese milkfish.

He still is not sure how to make room for the long list of spices and seasonings local Filipinos just asked him for. For the non-Asians who seem to be shopping here more and more, he figures it is the healthiness of Asian food that they like.

“Most of the Chinese people are skinny,” Ni said.

Linda Feldman said she also comes for the adventure, beautiful shiitake mushrooms and “incendiary” Korean chili paste. “I’m a curious eater,” she said, setting down her shopping basket to survey the options. “It ain’t just meat and potatoes.”

On the wall by the cash registers, fish tanks hold whatever interesting seafood-related things Ni finds in New York. There were lobster and abalone snails scooting by with fluttering edges like big eyelashes.

An Alaskan King crab, $300 at $44 a pound, filled the space and seemed to tap dance from each corner.

Guo snapped a picture with a pink phone bouncing with a big pink powder puff pompom. She would post this giant American novelty on Chinese Twitter.

It had been two years since her first trip to the Hoowa and she had just finished her master’s in education for teaching English. In a couple of weeks, she would be back home.

On this trip to the Hoowa she was still after the ingredients for her usual favorite: Things to cook in “hot pot,” the simmering soup she likes with hot peppers, tofu, meatballs and cabbage.

Despite the local shortage of good karaoke bars and Chinese restaurants, Guo, whose Chinese name Ruize means happy and good luck, had found a lot of local novelties to appreciate since she first moved here:

Blue, blue sky, fresh air, the American style of not judging people and accepting differences.

In the food department, China still wins. The fast food American cuisine she got to know didn’t come close. At one of her last meals with her boyfriend and roommates in her suburban apartment, she plucked out bites with chopsticks from the broth that bubbled from a burner set in the middle of the kitchen table.

In Buffalo, she said while dining on noodles, dumplings and strings of enoki mushrooms, the Chinese supermarket is very necessary.

********************

Hot Pot

This recipe for hot pot was adapted from directions by Jeffrey Jun Pang, a visiting Chinese student at the University at Buffalo

What you need and can find at Asian markets:

1 medium-size, medium-depth pot.

Some seasoned hot pot soup base, such as Little Sheep brand. The packages contain small packets of base and you won’t need to use all of it.

Small dried chili peppers can also be added.

Other ingredients to consider:

1. Frozen food: Meatballs, crab meat, egg dumplings, fish dumplings and even tofu, which has a pleasantly chewy texture after its frozen.

2. Thinly sliced, bite-sized pieces of raw meat: chicken, beef, lamb

3. Lunchmeat

4. Clear “cellophane” noodles, such as mung bean

5. Any vegetable, cut into bite-sized pieces: Greens, cauliflower, cabbage, broccoli, mushrooms

Fill pot half or three-quarters full, pour in soup base and boil. Add ingredients group by group in the order above, returning water to a boil before adding the next: Put in frozen food, return to boil. Add raw meat, return to boil, etc. Lunchmeat does not need time to cook, but will flavor the broth when added.

Meal is usually eaten with the soup simmering on a gas burner set in the middle of the table. People take helpings with chopsticks and a mesh ladle, depositing food on a plate or bowl to cool briefly before eating.

Jun Pang adds: Do not put in too many hot peppers. They can be even more terrifying than SUICIDAL Buffalo wings. Dipping sauce is also recommended: A hot sauce or hoisin sauce. Some are specially designed for hot pot. But only dip a little. Otherwise, is either too hot or too salty.

Also, take noodles out of the pot soon, or they will swell and be difficult to remove.

[email protected] null