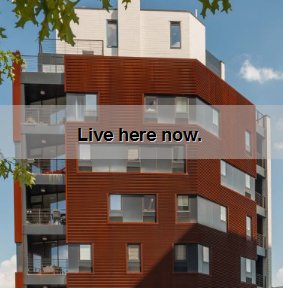

Back in late January, Inhabitat.com reported that 5 Pointz, the graffiti mecca in Long Island City, may be facing demolition by as soon as next year. Until now, owner Jerry Wolkoff had allowed the massive studio building to be used as a canvas by some of the best and most iconic artists of the genre.

The top of the building is rimmed by the names of legendary graffiti artists who have since passed away. But now, Wolkoff believes that rather than preserving the iconic artistic site, what the city really needs is some more luxury high-rise condos.

It’s not a done deal though, as Long Island City Councilman Jimmy Van Bremer urged activists to petition the city to make the building a historical monument. That’s nice, but the fact that the building is even on the chopping board is sickening, and it fuels the manic focus of profits at the expense of art and culture.

The argument over 5 Pointz’ demolition is nothing less than an argument about whether or not we want to preserve one of our most important contemporary art forms and historically enshrine this expressive phenomenon of ours for future generations to appreciate.

Graffiti is our current day’s folk-art expression. Certainly, its illegal nature ensures that it will always be controversial and that it will always exist on the fringe of an ordered, law-abiding society. I can’t even say that I support graffiti in all of its forms, a viewpoint that vehement defenders of the art might spit upon. But what is not debatable, I think, is that it is one of the most pervasive, unique, and iconic forms of spontaneous public artistic expressions of our generation.

Modern clothing, music, film, dance, and other visual arts have all been indelibly marked by graffiti’s influence. Knocking down a building with as beautiful a creative expression and as important a historical context as 5 Pointz’ is tantamount to ripping apart a Picasso painting to make room for a plasma-screen TV.

It’s not like there is no precedent for recognizing graffiti as a historically important artistic representation of our time. For example, all across the U.S., great care is taken to preserve Native American hieroglyphics. The same is the case for preservation of ancient cultures around the world.

In some of these cases, archeologists acknowledge that they have no way knowing if the art was “important” or not (as if that’s up to us to decide) – whether it represents a billboard or the fanciful scratching of one member of that society. The same artistic links exist between ancient “graffiti” and other visual arts that do today – Native American hieroglyphic imagery factors heavily into their folkways, as does graffiti in New York City.

The point is that we have always been interested in preserving a record of our own history – both in its grandest forms and its more plebeian forms. We are presented now with the opportunity to acknowledge and preserve our own artistic record of graffiti.

It isn’t just a matter of preserving New York’s artistic footprint, although this factors heavily into it. From the beautiful (and controversial) painted subway cars of the 1980s and 1990s to the rooftops lining the Brooklyn Bridge to today’s large, land owner-authorized murals, graffiti is a permanent part of New York City’s art scene.

But 5 Pointz’ importance extends beyond these city streets. 5 Pointz is crucially important to documenting graffiti culture. It also at least loosely represents graffiti artists and cultures worldwide, including international super-stars Basquiat and Banksy.

5 Pointz should not just be crucially important to us; this monumental artwork should be a focus of international concern. No one would knock down the Coliseum to build high-rises, it’s too valuable a monument for human art and ingenuity. So no one should knock down 5 Pointz either. It would be a grave disservice to the graffiti culture that enshrines this city.