“Hi Avonte, it’s mom. Come to the flashing lights Avonte.”

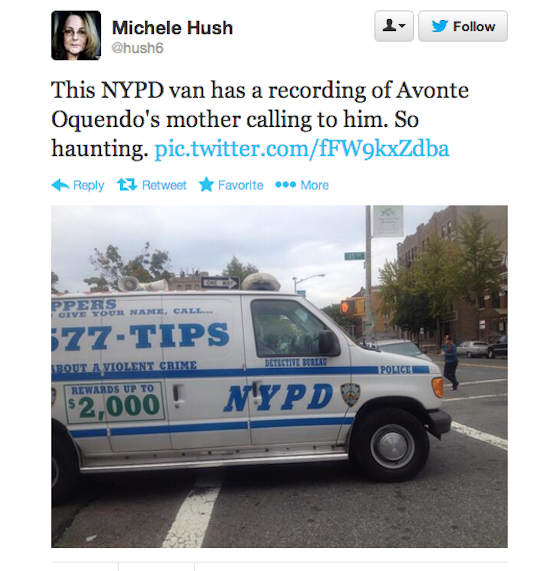

That was the message many New York pedestrians could hear blaring from NYPD vans in recent days, as one part of a mammoth effort to track down 14-year-old Avonte Oquendo. Since he went missing nearly two weeks ago after wandering away from his school in Long Island City, NY, police and volunteers have taken various steps to track Oquendo down: they’ve distributed flyers, scoured transit facilities, and made announcements on subway cars. Now, they’re playing a recording of his mother’s voice in an attempt to lure him to safety.

Trying to find any missing child can be a gargantuan, sometimes futile task. But police and volunteers are taking extra, unconventional steps to find Oquendo because his case is different in one vital way: Oquendo is severely autistic. “We worry about this kind of situation all the time,” says Dr. Gary Goldstein, chair of the Autism Speaks scientific advisory committee and president of the Kennedy Krieger Institute. “It happens far too often in this particular community.”

Video credit: DNAInfo.com

“We worry about this kind of situation all the time.”

Indeed, many of the traits that characterize autism also make it more likely that kids with autism will get lost — and that, when they do, there won’t be a happy ending. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2011 designated “wandering,” described as the tendency among individuals to stray from safe areas, as a “potentially life-threatening” aspect of autism spectrum disorders. The agency hoped that the designation would facilitate more data collection and greater public awareness around the issue.

However, some research on the prevalence of autistic wandering already exists. One 2012 study from Kennedy Krieger concluded that 49 percent of children with autism attempt to flee from a safe environment (like their home or school) — a rate that was four times higher than the non-autistic siblings of study participants. And data from the National Autism Association notes that the leading causes of death and injury among autistic children are drowning and traffic accidents. More often than not, both are due to a child wandering away: between 2009 and 2011, 91 percent of deaths among children with autism who wandered off was the result of drowning.

49 percent of autistic kids attempt to flee from a safe environment

Typically, Goldstein says, wandering is the result of a child seeing something that intrigues them (they’re often drawn to water) or trying to flee from an uncomfortable situation (like a crowded, noisy, or bright space). And because autism is characterized by “persistent fixation,” Goldstein adds, kids intent on fleeing will focus on that goal until they attain it. “If they get in their head that they want to bolt, they will keep trying over and over until they finally do it,” he says. “Just because they’re not speaking, doesn’t mean they’re not clever enough to trick someone and go for it.”

Indeed, as a handful of recent high-profile cases illustrate, instances of missing autistic children are all too common. Earlier this year, seven-year-old Alyvia Navarro bolted from her grandma’s home in Wareham, MA, and was found drowned in a nearby pond. In 2011, eight-year-old Robert Wood wandered away from a park and was found one week later huddled in a remote creek bed. And in an incident that later inspired a feature-length film, Brooklyn teenager Francisco Hernandez, Jr. spent 11 days hiding in the New York subway system before being located.

In Oquendo’s case, it remains unclear why he wandered off — or whether lax supervision was to blame. A school surveillance camera shows the teen speaking to a school safety officer at the front door, before turning around and exiting the building through an unlocked side door. Now that he’s gone, trying to find the boy — who measures 5 foot 3 and was last wearing a gray striped shirt with black pants — has thus far proved extremely challenging. Oquendo is non-verbal, meaning he wouldn’t respond to someone calling his name, and he tends to retreat from stimuli. His mother, Vanessa, described her son as having “the mental capacity of a seven- or eight-year old.”

“He doesn’t know that, you know, ‘I can get hurt in the street, someone can grab me and take me’,” she told reporters earlier this week. “He doesn’t know that. He doesn’t know fear.”

“He doesn’t know that. He doesn’t know fear.”

The NYPD is taking some steps that have characterized other searches for children with autism who go missing. Authorities make special efforts to search small, enclosed, isolated nooks where a child might be hiding. They also tend to avoid using sirens or dogs, as both risk provoking fear. Anyone who spots Oquendo is advised not to intercept him. Instead, law enforcement ask that individuals call authorities and then follow the child. And while Goldstein has never before heard of using a mother’s recorded voice, he describes the strategy as “a very novel, very clever one.”

Other than constant supervision and enhanced security, parents and teachers have few options to keep high-risk kids from straying. The Kennedy Krieger Institute is currently seeking funding for GPS bracelets that would, Goldstein hopes, offer a more foolproof means of locating kids like Oquendo when they go missing. For now, however, the search for Oquendo continues. “I just need to find my son because he needs his family; he cannot fend for himself out there,” his mother said. “This is just the hardest thing to have your child disappear, and you cannot bring him home with you.”