The 56.4 million visitors to New York City last year had their choice of hotel rooms—102,000, in fact, with thousands more on the way. The city’s manufacturing businesses only wish they had so many places to hang their hats.

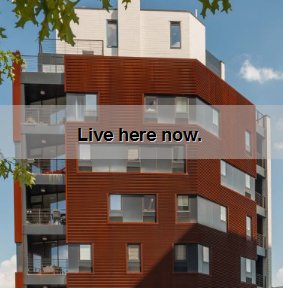

As hotels gravitate to über-trendy areas like Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Long Island City, they’re pushing out small businesses that have made those industrial neighborhoods their home for decades. Companies are facing outright displacement or tripled real estate prices, the unwelcome consequences of the ongoing hotel boom. Those businesses that have not been forced out yet fear a move to Long Island or New Jersey is inevitable.

“If you pick me up and move me out to Ronkonkoma, I could get a couple of acres very cheaply by comparison, but I’ll have trucks on the road clogging the expressway to do those jobs we service now from right across the river,” said Kenneth Buettner of York Scaffold Equipment Corp., an 87-year-old, third-generation family business. York Scaffold is currently based in the industrial Ravenswood section of northern Long Island City. “I’m not averse to change, but the problem is you need space for everything.”

For hotels, there’s space aplenty in industrial zones. Real estate prices are cheaper than in central neighborhoods such as Times Square and SoHo, and visitors are now much more willing to decamp to north Brooklyn and Queens than they were decades ago, when the pro-manufacturing zoning laws were written. Back then, those areas were noisy and gritty; not so now. Williamsburg, of course, is now a vibrant hotbed of creativity that lures busloads of tourists and Manhattanites every weekend.

Unintended consequences

Since 2007, at least 11 hotels have opened in industrial business zones, and another 16 are on the way, according to a recent Pratt Center for Community Development study funded in part by the New York Hotel and Motel Trade Council. IBZs were established by the Bloomberg administration to “protect existing manufacturing districts and encourage industrial growth citywide.”

Similarly, in older M1 zones—areas for light manufacturing—at least 115 hotels are up and running, and 75 more are in the pipeline. There are 24 hotels in Long Island City alone. Whatever the zoning laws were once meant to accomplish, they’ve long since stopped being useful.

The hotel growth influences how property owners “set their price and expectations for their own property,” said Adam Friedman, Pratt’s executive director. “It has a destabilizing effect on the real estate market.”

Further, Mr. Friedman said, manufacturing tenants may be less inclined to invest in their current properties, purchasing new equipment or hiring new staffers, if they believe they will soon be moving on.

There are still 2,100 manufacturing firms in Long Island City, and many of them employ neighborhood residents. The area cannot afford to let them all go. “We need thoughtful development planning around how to make sure, for the sake of the long-term viability of the city, that we have spaces for these uses,” said Elizabeth Lusskin, president of the Long Island City Partnership.

Room for the Inns

Hotels, by Industrial Business Zone

NeighborhoodExiting hotelsPlanned hotelsLong Island City, Queens

24

17

Garment center, Manhattan

31

101

Williamsburg, Brooklyn2

3

9

Greenpoint, Brooklyn

1

3

Sources: Long Island City Parntership, Garment district NYC, Pratt Center for Community Development

1 Estimate.

2 Data from spring 2014

At a breakfast late last week, Mayor Bill de Blasio acknowledged the dilemma. “We regard manufacturing as a crucial piece of our economy,” he said. “There are other parts of the city that are great manufacturing centers and need to remain so.” He said he will soon lay out a vision for the future.

That won’t help the companies that have already picked up stakes. Tri-State Biodiesel, an 11-year-old firm that collects used cooking oil and turns it into fuel, left North Williamsburg six years ago for the Bronx’s Hunts Point. The neighborhood is now home to, among others, the Wythe Hotel and McCarren Hotel Pool.

York Scaffold may be staying put, but it won’t be expanding any time soon, either. Mr. Buettner, who co-owns the company with his sister Kathryn, blames the new hotels for York’s inability to buy nearby property. Three new hotels have opened within blocks of his office and warehouse, which are in an IBZ, he said.

Another is planned for a 5,000-square-foot yard that Mr. Buettner once rented with hopes of purchasing. In the end, he couldn’t afford anywhere near the $1.2 million price. Worse, Mr. Buettner, who employs some 60 staffers, has had to decrease his product offerings.

He knows he’s in the midst of an us-versus-them battle. “Some of us are not the kind of neighbors you want next to hotels—no matter how quiet we are, we’re noisy if you’re sleeping next door,” he said, citing early-morning truck loading and the general cacophonous soundtrack of work. “Hotels don’t need permission or variances to commit to an industrial area, but they’re really not a good fit.” Though current zoning allows for hotels, critics believe hoteliers should be required to get special permits.

Inhospitable climate

Moving out of the garment center isn’t in the cards for James Mallon of 25-year-old InStyle USA, a sportswear maker for brands including Theory and Saks. The 10-year lease on his 15,000-square-foot space on West 36th Street is up in 18 months even as he’s watching hotels sprout up all around him.

Though he’s worried his $22-per-square-foot rent will increase by as much as a third, he’s reluctant to find a cheaper neighborhood because his business benefits from its proximity to pleating and belt-making companies. It doesn’t help that he invested $400,000 in his space.

“I’m a good tenant. We pay our rent and have a very clean operation,” said Mr. Mallon, who said he will have to ask his customers for a 30% raise to afford any rent increase.

The irony is that the uptick in hotels comes at a time when the city may already be overstocked. In January, average daily room rates for the New York market fell by a whopping 8.6% over January 2014, to $190.16, according to hotel research firm STR. Average revenue per available room was down 12.9% over the year-earlier period, a decline not seen in other major metropolitan areas, such as Chicago and San Francisco. Apartment-share sites such as Airbnb and HomeAway are only adding to the glut.

“No one is concerned that we don’t have enough hotels–some may argue that we have too many,” said Josh Gold, political director at the Hotel and Motel Trade Council. “So to have hotels crowding out other uses, like manufacturing, that the city wants to grow … is a policy concern the city should be paying attention to.”